The Great Bank Unbundling

This is a deep dive Kyle Harrison and I published for Contrary Research unpacking Banking-as-a-Service. You can find the deep dive here, or read it below!

About The Authors

Rayan Malik: Research Fellow @ Contrary. Rayan has published deep dives into several companies across fintech infrastructure and embedded finance. He is currently a researcher for the Andreessen Horowitz podcast and will be joining Insight Partners this summer. Computer Science & Economics at Duke.

Kyle Harrison: General Partner @ Contrary. Kyle leads Contrary’s investing efforts for companies at Series A and beyond. He’s previously worked at firms like Index and Coatue investing in companies like Plaid, Toast, Persona, and Lithic that have all touched aspects of embedded finance.

Special thank you to Ian Kar at Vol. 1 Ventures for his support, and to all the founders and investors who contributed to this report: William Hockey at Column, Jacqueline Reses at Lead Bank, Nikil Konduru and Bo Jiang at Lithic, Sankaet Pathak at Synapse, Peter Hazlehurst at Synctera, Chris Dean and Courtney Sato at Treasury Prime, Itai Damti at Unit, Amit Kumar at Accel, Eric Kaplan at Bessemer Venture Partners, Sheel Mohnot at Better Tomorrow Ventures, Tim O’Shea and Jonah Crane at Klaros Group, and Amias Gerety at QED Investors. Additionally, thank you to Jason Mikula and Alex Johnson for their continued coverage of this space.

Actionable Summary

Fintech has played out in three acts to become what it is today: (1) digitization, (2) disintermediation, and (3) embedded infrastructure.

In Act 1, the focus was on making digital banking possible and mainstream. In Act 2, banking became less centralized and started showing up in disintermediated financial apps. Finally, in Act 3, the emphasis shifted to establishing banking partnerships as infrastructure, which enabled disintermediation at scale. This enabled non-fintech companies to also offer financial services. That was the vision behind Banking-as-a-Service.

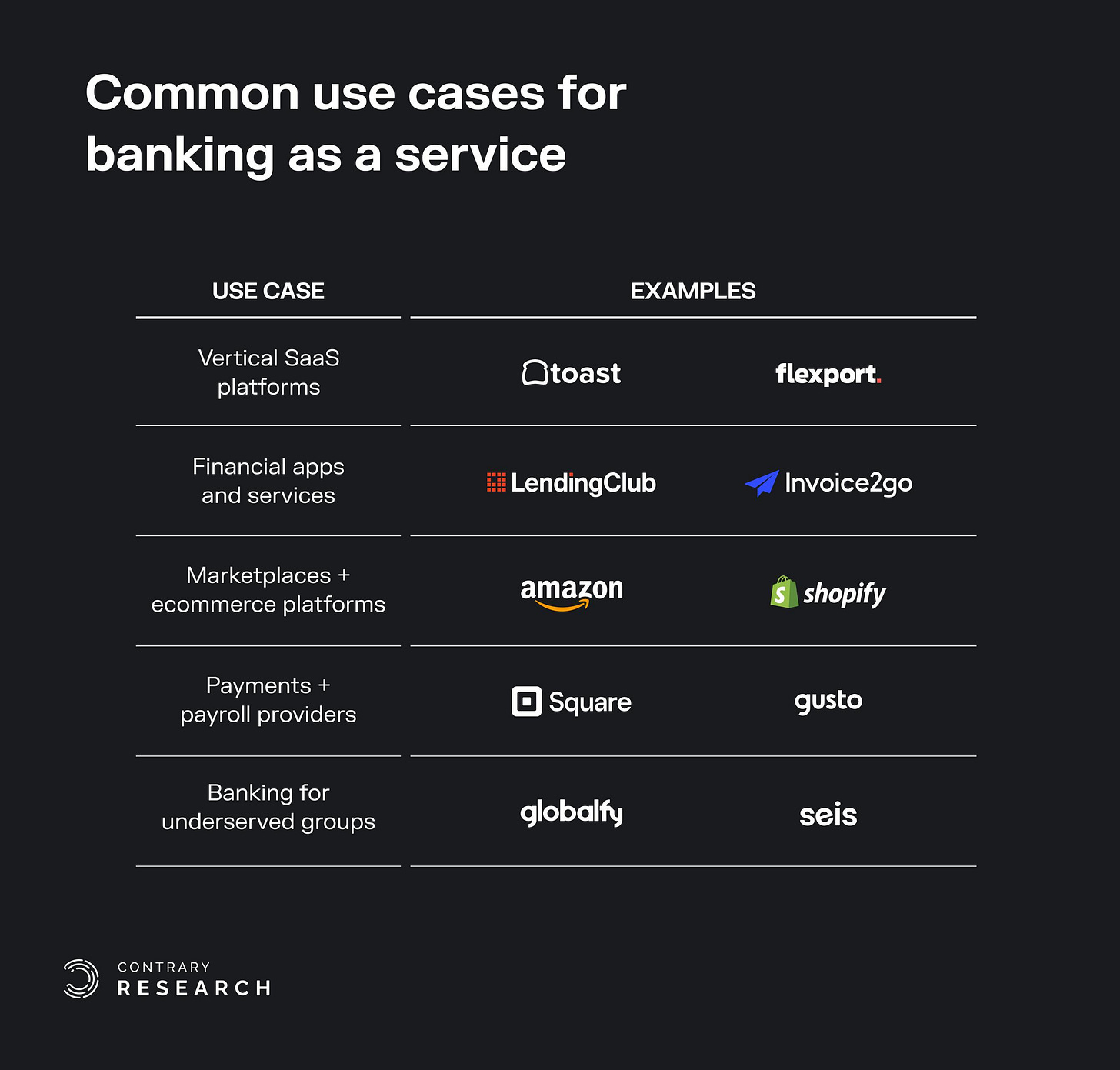

As Act 3 of fintech has played out, nearly every successful verticalized software product, from Toast to Shopify, has attempted to embed financial services into its core product offerings. For example, 83% of Toast’s 2021 revenue came from financial services alone.

The term “embedded finance” as we use it encompasses any company's attempt to weave financial services into its offering, typically in software. Financial infrastructure companies are those that attempt to enable a company’s capability to offer financial services. Embedded finance represents a meaningful new revenue opportunity for a large number of technology companies.

As more technology platforms started looking for ways to expand their revenue streams by broadening their financial service product offerings, many community banks (e.g. banks with less than $10 billion in assets) continued to see contracting revenue. Historically, community banks have used their physical footprint in specific geographies to compete against larger banks. But in a digital world, a physical branch can be a diminishing asset.

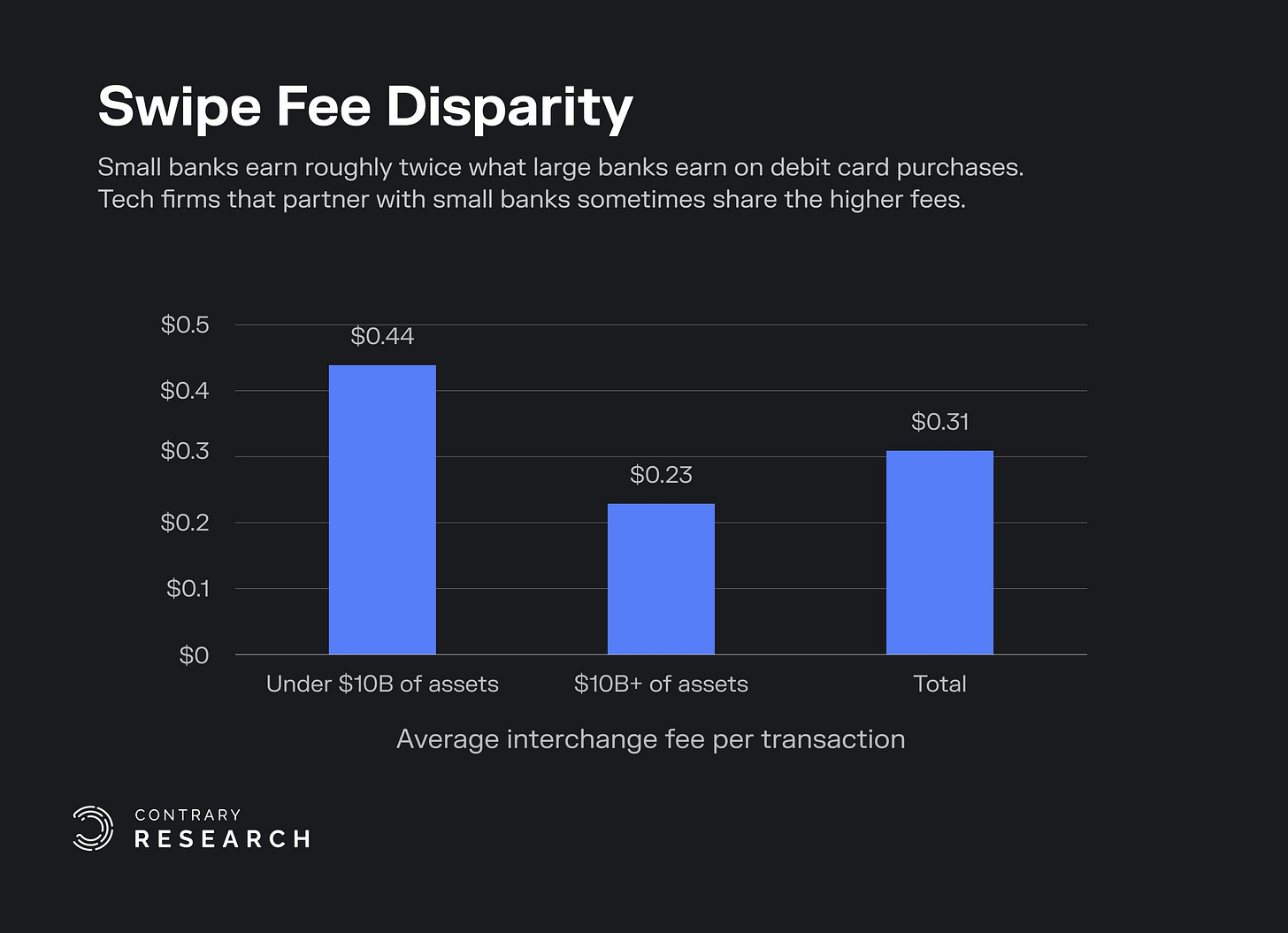

In 2010, the Durbin Amendment was passed as part of the Dodd-Frank Act. The amendment capped the interchange fees that large banks could receive, but banks with under $10 billion in assets were exempt, allowing them to chase larger revenue opportunities.

Direct partnerships with software companies presented these community banks with a more cost-effective distribution channel than competing directly with larger banks. These software companies already had a captive audience of users interested in financial services and community banks had already been offering these financial products for decades.

However, there were fundamental time and resource constraints. Building infrastructure directly on a bank took between 15-18 months and ~$2 million to launch a product, with ongoing annual costs of about $2.5 million to maintain the product.

This cost and complexity of working with a bank, combined with the size of the opportunity of a successful fintech partnership, gave rise to a category that became known as Banking-as-a-Service (BaaS). Instead of non-bank companies needing to build out entire backend infrastructure, or banks having to create APIs to let non-bank companies connect to their core systems, both sides could rely on a BaaS provider to provide the technology that enables non-banks to partner directly with banks to embed financial services.

But despite the growing interest in BaaS, enabling infrastructure with non-bank companies was inherently risky for banks. These companies moved quickly, and operated creatively, while banks were traditionally slow-moving and conservative. This naturally created a fundamental misalignment of incentives, leading to some early banks receiving consent orders as non-bank companies grew too quickly without the appropriate compliance oversight.

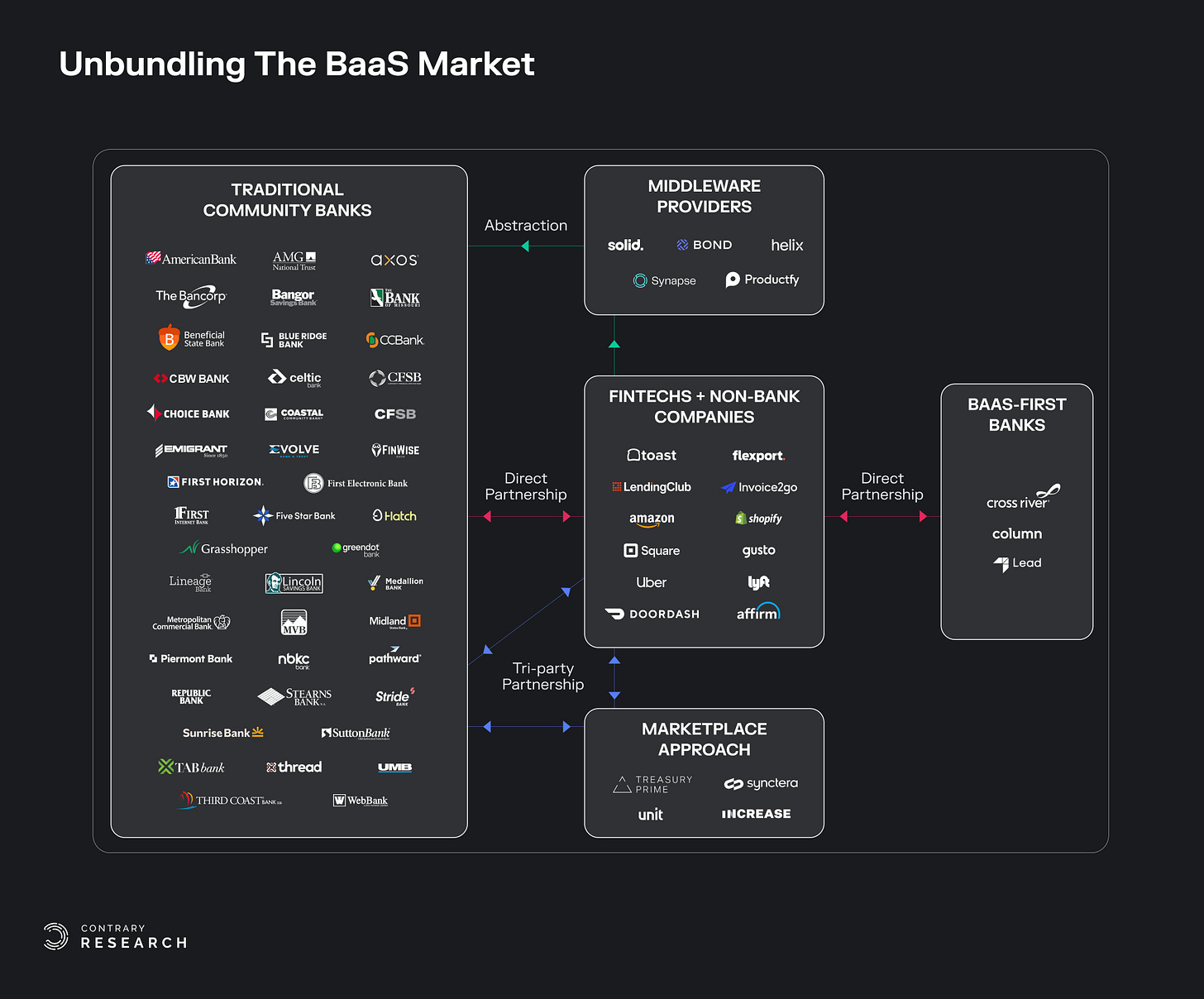

Addressing these risks has resulted in the emergence of several different approaches and categories within BaaS: (1) traditional community banks, (2) middleware providers, (3) bank marketplaces, and (4) BaaS-first banks.

Traditional community banks are banks with less than $10 billion in assets that are engaging in BaaS, yet have not historically been tech-first banks.

Middleware providers are BaaS companies that build technology and, combined with a network of banks and non-bank companies, act as an abstraction layer between a partner bank and a non-bank company. In these partnerships, partner banks and non-bank companies do not have a direct relationship, and the middleware providers take on many of the compliance responsibilities.

Bank marketplaces are BaaS providers that enable direct partnerships between multiple partner banks and non-bank companies via a marketplace.

BaaS-first banks are tech-native community banks that have built out the required technology stack to offer a BaaS program. These banks work directly with fintechs and prioritize BaaS as their core growth strategy.

There are still several obstacles in the way of embedded finance reaching its full potential, from regulatory issues and rising compliance costs to an overall slowdown in the funding markets for fintech companies.

However, while regulatory obstacles have led to some short-term challenges, especially for middleware providers, it has resulted in the industry becoming ‘fitter’ with many key players now emphasizing the importance of direct partnerships between fintech companies and banks.

In 2024, it has become increasingly clear that banking-as-a-service may give way to a new framework for banking infrastructure. That framework will likely involve direct, multi-bank partnerships. As a result, BaaS-first banks and bank marketplaces are emerging as promising candidates to power the rise of embedded fintech.

The Rise of Fintech

Innovation in finance didn’t just begin with the rise of digital payments and consumer apps. Instead, technology first started shaping financial markets as far back as 1865, when the first transatlantic cable reduced the amount of time it took to send a message between Europe and North America from 10 days down to mere minutes. That evolution continued on through other advances in communication technology, like the telegraph and Morse code, before the introduction of credit cards in the 1950s.

Next came the advent of ATMs in 1967, the establishment of cross-border payment protocols like SWIFT in the 1970s, and the first wave of banks using mainframe computers in the 1980s. These innovations all set the stage for banking to enter the digital age during the dotcom boom. Fintech, as it is known today, started to take shape at the turn of the 21st century. The evolution of fintech has played out in three acts: (1) digitization, (2) disintermediation, and (3) embedded infrastructure.

Act 1: Digitization

One of the first digital banking entrants was Stanford Federal Credit Union, which became the first institution in the US to offer online banking in 1994. Wells Fargo followed suit in 1996, becoming one of the first major national banks to move online. Yet, while the dotcom era ushered in an increasing number of financial services companies using technology, the use of financial technology itself was still in its infancy.

By the end of the 20th century, the first wave of fintech was gaining steam as financial services started to move online. In 1999, Elon Musk was building the original X.com. Its pitch was to become “a full-service online bank that provided checking and savings accounts, brokerages, and insurance.” Musk believed people were ready to begin “to use the Internet as their main financial repository.”

Yet while early tools like X.com and PayPal enabled early online payments, such payment solutions were a far cry from a full digital bank. Instead, the first meaningful digital banks grew out of some of the traditional players. Capital One and ING were founded in 1988 and 1991 respectively. Both played an important role in pushing digital banking forward. ING experimented with “direct banking” in the 1990s by offering services that didn’t require a customer to go to a bank branch, and could instead be accessed over the phone, or eventually online. ING launched the concept as ING Direct in the US in 2000.

From 2000 to 2011, ING Direct grew to 7.6 million users and $83 billion in deposits before it was acquired by Capital One for $9 billion. In part, the deal was driven by required restructuring resulting from the global financial crisis (GFC) in 2008. After the GFC, public sentiment shifted drastically against large banks. As a result, the opportunity for disintermediation began to increase.

Act 2: Disintermediation

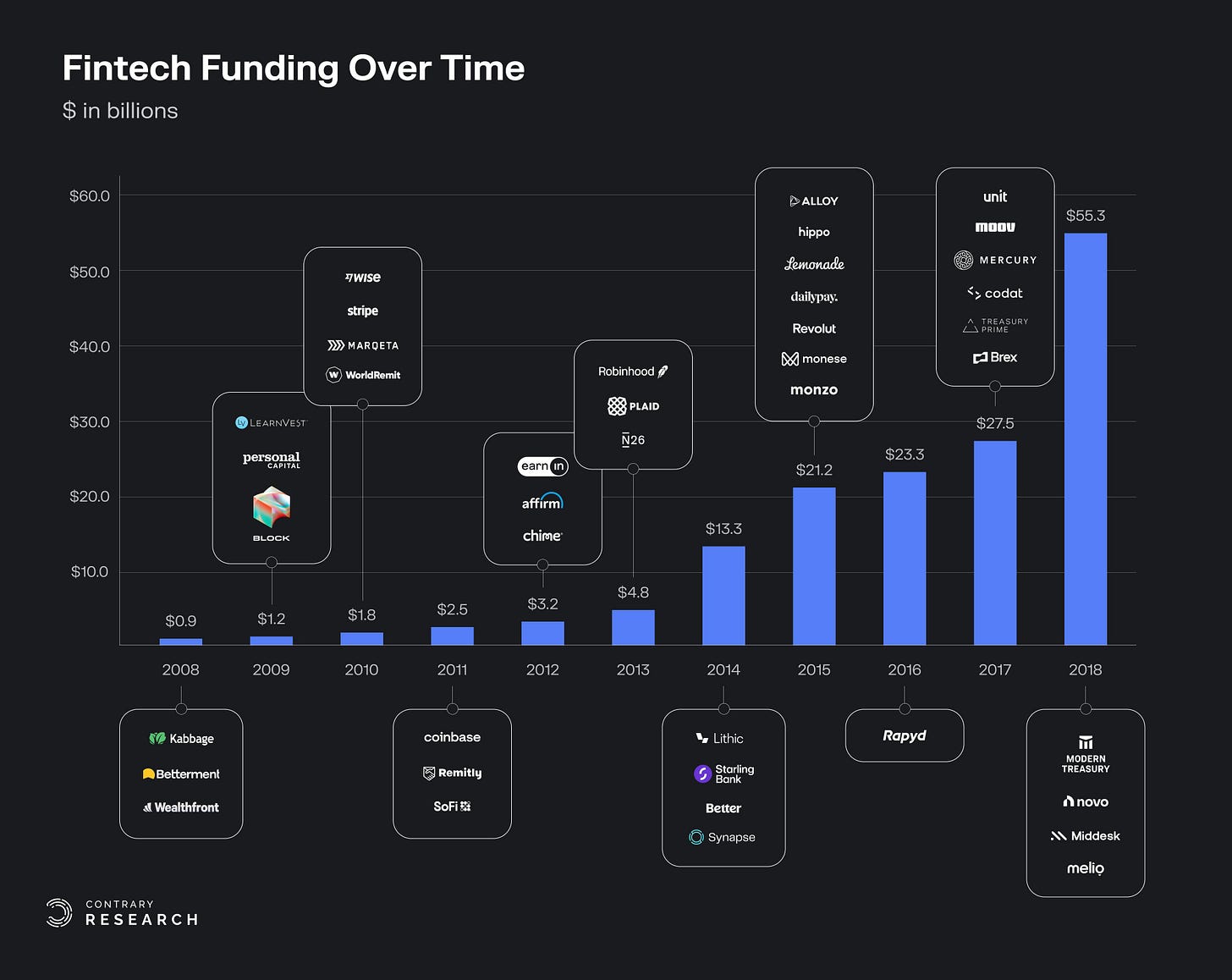

The combination of factors like meaningful distrust in large banking institutions post-2008, the release of the iPhone in 2007, and the creation of Bitcoin in 2008 created a prime environment for the “era of the startup” and the rise of fintech as we know it. Between consumer distrust and increased competition from digital banking, banks began to see rising customer acquisition costs into the early 2010s.

From the end of the dotcom era to the early 2010s, consumer-facing financial apps like Mint.com, Pageonce, and BillTracker were also becoming popular. At the same time, issuer processors, like Galileo and Marqeta, founded in 2000 and 2010 respectively, realized they could provide fintechs with direct access to services from Visa and Mastercard. This meant they could help consumer-facing financial apps simplify their infrastructure, and expand to offer services like card programs. As a result, a wave of new banking products emerged and began to attract an increasing amount of venture capital.

Act 3: Embedded Infrastructure

As providing financial services became a bigger opportunity for companies, it slowly became clear that early fintech startups were having to reinvent the wheel when it came to building infrastructure to support the financial services they offered. This complicated infrastructure significantly increased fintech companies’ time to market and was often quite expensive. Platforms like Stripe, Plaid, and Lithic, founded in 2010, 2013, and 2014 respectively, were built to address this problem and provide the necessary infrastructure to enable fintech products to be built faster and cheaper.

The goal of these new infrastructure platforms was to provide a one-stop experience for fintech companies to access partnerships with banking license holders, card networks, and third-party issuer processors that typically required a lot of heavy lifting. Essentially, the infrastructure provider could provide access to fully unbundled financial services, like cards, crypto trading, brokerage, deposits, and others. The backend for these services could then be more easily accessed via API.

This emergence of fintech infrastructure that could be embedded within an existing consumer application was the answer to the infrastructure challenge experienced by companies in Act 2. Banks increasingly realized they were better at providing and managing financial products, and consumer applications were often better at managing the customer experience. Embedded infrastructure leveled the playing field, and made the competitive landscape in fintech less about feature parity; with embedded infrastructure, consumer applications could offer the same features at a lower cost because of these financial infrastructure companies. Instead, the emphasis for these platforms became more about customer experience.

In an interview with Contrary Research, Amias Gerety of QED Investors, described it this way:

“Embedded finance is not a feature parity war. It is about this idea that I want to bank inside of other consumer experiences that have more emotional connection and business connection.”

In summary, in Act 1, the focus was on digital banking simply becoming mainstream, while in Act 2, the ecosystem evolved to focus on banking becoming less centralized and showing up in disintermediated financial apps. Finally, in Act 3 the emphasis shifted to establishing banking partnerships as infrastructure, which enabled, at scale, the disintermediation of financial services. That was the inherent vision behind Banking-as-a-Service.

A New Paradigm: Banking-as-a-Service

From Technology To Finance

As Act 3 of fintech has played out, nearly every successful verticalized software product, from Toast to Shopify, has attempted to embed financial services into its core product offering. For example, 83% of Toast’s 2021 revenue came from financial services alone, with the majority derived from its payments products. Put simply, embedded financial services presented an opportunity for software companies to unlock new revenue streams via interchange, improve retention, and create a more comprehensive user experience.

For example, in 2019, Uber formally announced the launch of “Uber Money”, a team within Uber dedicated to creating a suite of financial products for drivers to access real-time earnings via an Uber-branded debit card. By launching this branded card, Uber not only unlocked a slice of interchange revenue each time a driver spent money using the card, but also increased the expected lifetime value of Uber Drivers via platform lock-in.

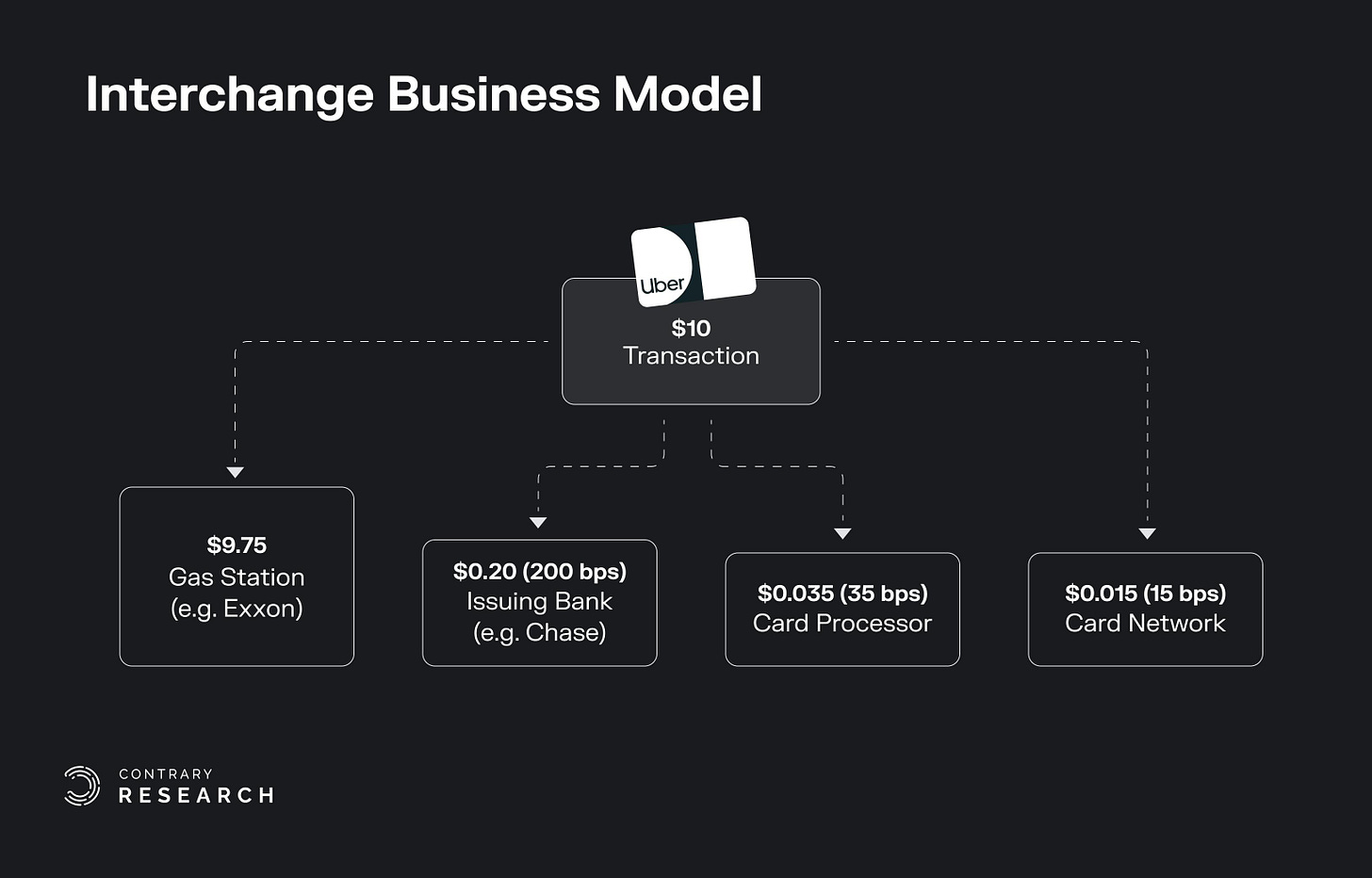

Uber was able to unlock interchange revenue by partnering with a sponsor bank, like Green Dot Bank, to launch an Uber-branded debit card. Before Uber Money, when Uber drivers purchased gas for $10 using a Chase card, for example, the payment flow paid out as follows:

Traditionally, out of a $10 transaction, the gas station would earn $9.75, the issuing bank (Chase) would earn 200 basis points (bps), or $0.20, while the card processor and network would each earn per-transaction fees. So every time an Uber Driver spent money at a gas station, Chase was making money.

But with the launch of Uber Money, that 200 bps went back to Uber. If an Uber driver used their Uber-issued debit card, that interchange revenue would get split between Uber and Green Dot Bank. Unlocking such revenue can be significant at scale for non-bank companies. For example, it is estimated that Target’s net profit in 2022 would have increased by 65% if interchange fees were eliminated.

Additionally, successful companies typically have a unique advantage in their respective spaces. For example, no company has more data on part-time drivers than Uber. As a result, Uber has been able to expand into other offerings like car rentals for drivers, insurance, and instant cash-outs. The same is true on the consumer side; by offering an Uber Credit Card to its 9.4 million monthly active users, Uber has unlocked another meaningful revenue opportunity.

Beyond incremental revenue, financial services also provides benefits in terms of user experience and retention. In an interview with Contrary Research, Peter Hazlehurst, who previously led Uber Money and is now the co-founder of Synctera, discussed the opportunity that foraying into financial services offered Uber:

“At Uber, we had a huge community of drivers that had below-par banking relationships. It was a no-brainer to help our drivers get a better, personalized banking experience that made their lives easier. We knew we could save our drivers significant money and time by building a better solution tailored to them. We were also spending a significant sum in driver incentives to recruit a driver, so it was definitely a win-win to offer them a better banking experience as an added incentive to be on the platform. That’s why we created Uber Money. In general, fintech is about a combination of building a new revenue line and increasing retention of existing customers.”

However, despite the benefits that companies like Uber, Toast, or Shopify can get from expanding into financial services, there is still one fundamental constraint that prevents them from providing financial services themselves: a bank charter. In the US, to gather deposits or offer lending products, you are required to have a banking license. Yet, the process to acquire a license is not only long and expensive, but it also requires the completion of several complex tasks, such as:

Build a core banking system to log and track money movement

Create and maintain payment integrations to enable money movement

Hire a compliance department to work with regulatory bodies

Build software for fraud and anti-money laundering (AML)

Create a data pipeline to offer users new products

Create a governance structure to conform to the bank rules

Manage balance sheet and company financials to account for bank equity and risk guidelines

And these tasks listed above just represent a small fraction of the work associated with becoming a bank. As a result, acquiring a bank charter is often a multi-year process that requires an in-house banking team, a heightened level of compliance and risk controls, governance that includes banking regulators as partners, and a significant amount of financing with a clear near-term path to profitability. Further, regulators are generally opposed to non-bank companies attaining a charter, adding a layer of friction to the entire process. Consequently, this means that attaining a banking license is not typically a viable option for non-bank companies, both in terms of time and cost.

The Plight of Community Banks

However, while large technology platforms were looking for ways to broaden their product offerings to include financial services, many community banks (e.g. banks with less than $10 billion in assets) continued to see contracting revenue. Historically, community banks have used their physical footprint in specific geographies to compete against larger banks. But, in a digital world, a physical branch can be a diminishing asset. Smaller banks are seeing their infrastructure advantage and margins gradually erode as a result.

Interest income comprises ~75% of a community bank’s revenue. As digital banking has increased the competition between community banks and larger banks, the margin on that interest income has begun to fall, leading to reduced deposits. In 2003, banks with less than $10 billion in assets controlled ~38% of all aggregate deposits. Just 20 years later, in 2023, they only controlled ~17% of total deposits. One caveat here is that the Federal Funds Effective Rate was also cut significantly between July 2019 to April 2020, and remained at 0.08% until February 2022. This led to a compression in net margins across many banks, significantly contributing to falling deposits and interest income.

But, regardless of the cause, this shift meant that the biggest banks got bigger, and the smaller banks had to get creative. Jason Mikula described the typical thinking inside a community bank this way:

“If you're a community bank, you're thinking: We've reached the limits of what we can do to grow within our geographic community because now everything is digital, and young consumers are not coming into the branch. We're starting to see that shift in behavior. The key question is: How can we attract new customers into our organization?”

The most valuable asset community banks still owned was a banking charter, which enabled them to provide the financial services that larger technology platforms were desperate to expand into. This created a perfect opportunity for a partnership; technology companies could expand into financial services, and community banks could benefit from the growth in deposits that these partnerships would provide.

The Durbin Amendment

In the same way that the GFC created the path for financial applications to disintermediate some of the services of a traditional bank, it also created the perfect opportunity for community banks to get into the business of fintech.

In 2010, the Durbin Amendment was passed as part of the Dodd-Frank Act. The amendment capped the interchange fees that large banks could receive to $0.21 + 0.05% of a transaction. However, the amendment provided a critical exemption for banks with under $10 billion in assets, allowing them to charge $0.20 + 1.05% per transaction.

The allowance for smaller community banks meant that they had a meaningful revenue opportunity if they could partner with software companies. For some, that revenue could come from interchange if the software partners had access to large card spend, like Ramp* or Brex. For others (including the majority of community banks) that revenue would come from deposit volumes that could be acquired more efficiently by working with software partners. As a result, partnering with tech companies like Uber was the perfect path to accessing more customers quickly.

Specifically, direct partnerships with software companies presented community banks with a more cost-effective distribution channel than competing directly with larger banks. Software companies already had a captive audience of users interested in financial services and community banks had already been offering these financial products for decades. Matthew Smith, Chief Digital Banking Officer at Webster Bank, described it this way:

“What’s interesting is you're not doing anything that's vastly new; these partnerships are just a different application of what you already do. We already provide deposit products to businesses. We already provide deposit products to consumers. That is not foreign. What’s foreign for us is having somebody else be the frontend of it.”

Further, while community banks that partnered with companies running large scale card programs benefited from interchange revenue, the majority of community banks also saw an opportunity to benefit from fast deposit growth. By entering into fintech partnerships with tech companies, community banks could reduce their direct customer acquisition costs from an average of $100-$200 to as low as $5-$35, while simultaneously growing deposits.

But, while the cost-cutting potential was compelling, such partnerships proved to be difficult to scale. The first generation of companies to try this, such as early neobanks like PerkStreet and Simple in 2009, were forced to build connections to legacy banking systems, which were limited in terms of account creation, KYC/AML, and fraud prevention. As a result, the quality of the financial products they could offer was similarly limited by the technological capabilities of the sponsor banks.

The second generation of tech companies to build financial services, such as Chime or Current, built entirely new backend technology from scratch, sometimes including complex financial ledgers. While this approach reduced their dependency on partner banks, the cost of building such infrastructure was significant and dramatically increased the company’s time to market.

Even once backend systems were built, tech companies still lacked the banking expertise to ensure that the platforms they built were compliant. Additionally, there were high costs in time and resources. Working directly with a bank took between 15-18 months and ~$2 million to launch, with ongoing annual costs of about $2.5 million. Even for larger tech companies, such costs were prohibitive, let alone early-stage startups.

Banking-as-a-Service

The complexity of working with banks, and the cost of building in-house infrastructure, combined with the size of the opportunity of fintech, gave rise to Banking-as-a-Service (BaaS) companies. Instead of non-bank companies needing to build out entire backend infrastructure, or banks having to create APIs to let non-bank companies connect to their core systems, both sides could rely on a BaaS provider to provide the technology that enables non-bank companies to partner directly with banks to embed financial services. Working with a BaaS provider reduced the time to launch a financial product from 18 months to two, and initial costs from millions of dollars to just $50K. In other words, BaaS made launching a financial product as a non-bank company viable.

From 2014, with the launch of players like Synapse and Uber’s Green Dot partnership, BaaS providers played a critical role in the embedded finance landscape, operating as middle agents that connected banks looking to offer financial services but didn’t have the technical capabilities to do so, with fintechs and non-bank companies that wanted to offer financial products but didn’t have a bank charter.

The BaaS Landscape

Since the emergence of the first BaaS providers, some of the world’s largest companies, from Amazon to DoorDash*, have worked directly with BaaS providers to launch financial products for their customers. As a result, the market has experienced significant growth, with some estimating that BaaS will represent a $7 trillion opportunity by 2030.

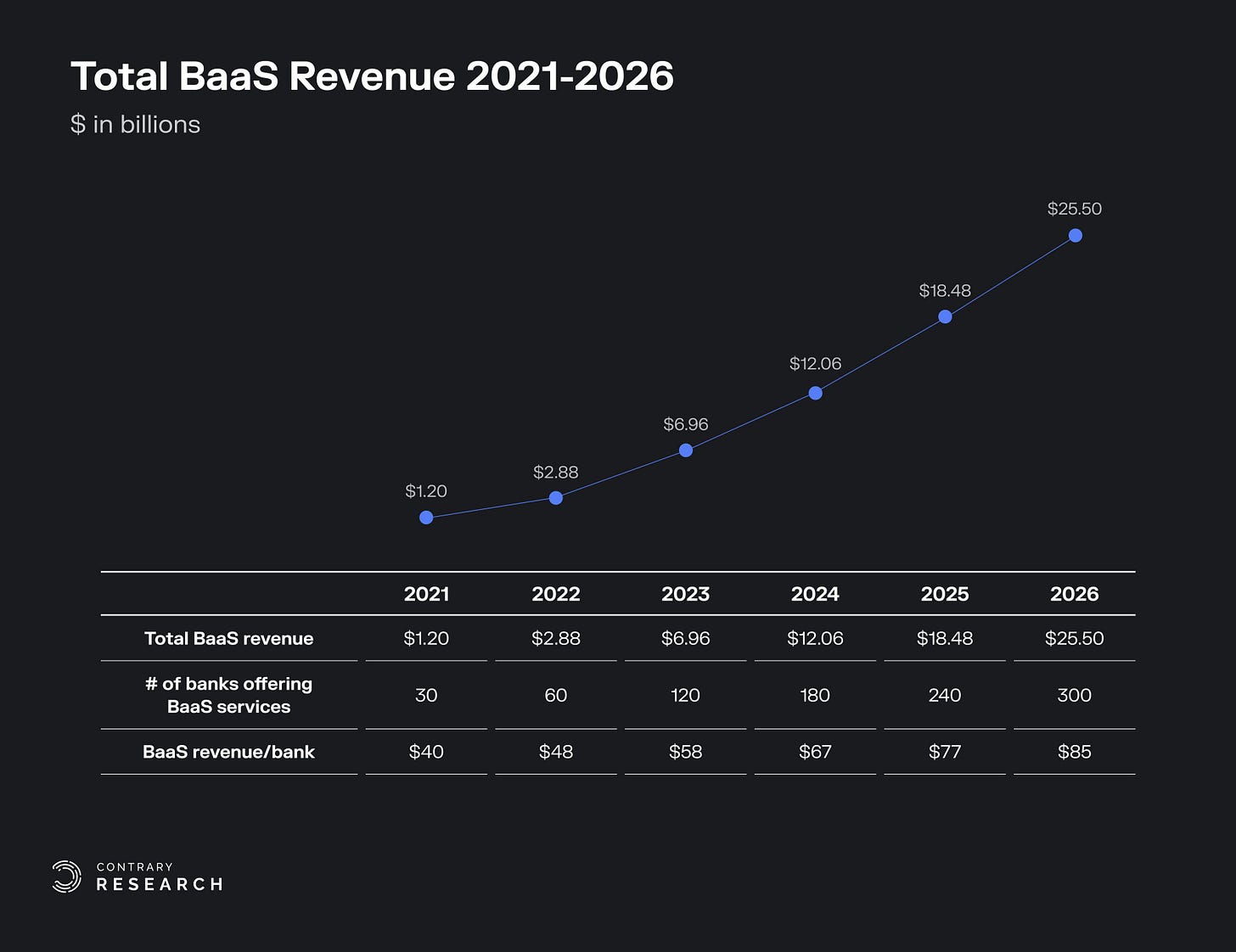

As the demand for embedded financial products has risen, it has also been met by an increased supply of partner banks engaging in BaaS. For example, in 2020, there were already more than “30 partner banks representing hundreds of fintech relationships and financial services.” In 2024, that number has already grown to ~120 partner banks.

Allowing Community Banks To Win

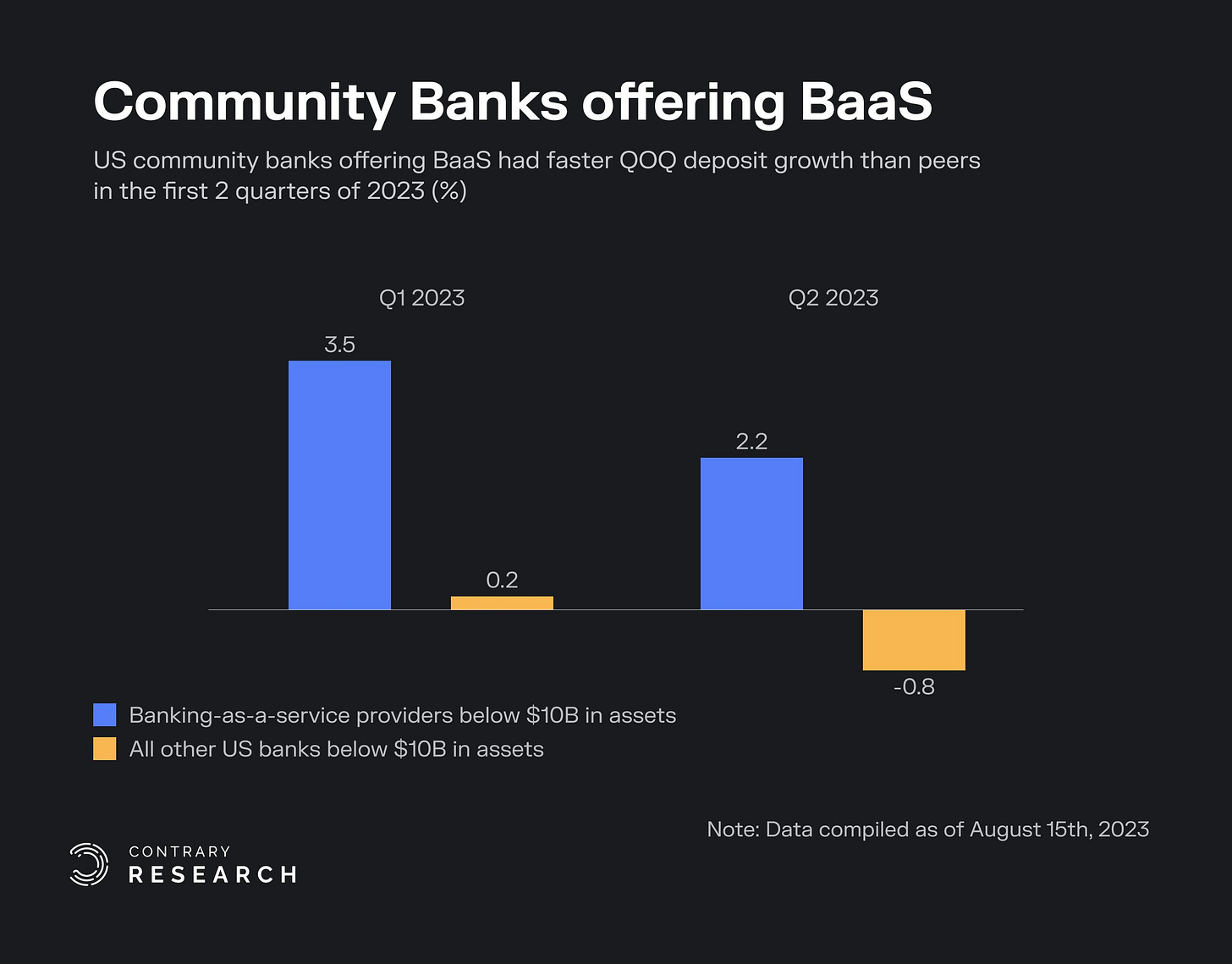

So far, community banks that are engaged in BaaS, like Green Dot and Cross River Bank, have benefited significantly from a rise in loans and deposits, as well as falling customer acquisition costs. This has enabled them to outperform the return on assets (ROA) generated by traditional banks. Between 2017 and 2019, partner banks in BaaS were operating “at profitability levels two to three times above average.”

The core driver behind this improved ROA is that community banks engaging in BaaS are outcompeting their peers as a result of their direct access to millions of customers via non-bank partnerships. The biggest revenue drivers are commercial loans and deposit growth. In fact, some of the highest ROA banks (WebBank, Celtic, CRB) are driven by lending, and often can’t even offer deposit accounts.

The data also reinforces the growth opportunity for community banks in BaaS. For example, in Q2 2023, community banks that supported BaaS experienced a median sequential deposit growth rate of 2.2%. In contrast, community banks that did not support BaaS experienced a decline in the growth of deposits by 0.8%.

This rise in deposits and higher ROA for community banks providing BaaS have ultimately made customer acquisition more affordable, allowing for growth where there had previously been stagnation. Each partner bank has varying revenue streams from BaaS depending on whether they support lending, consumer or commercial accounts, or large-scale card programs that drive interchange.

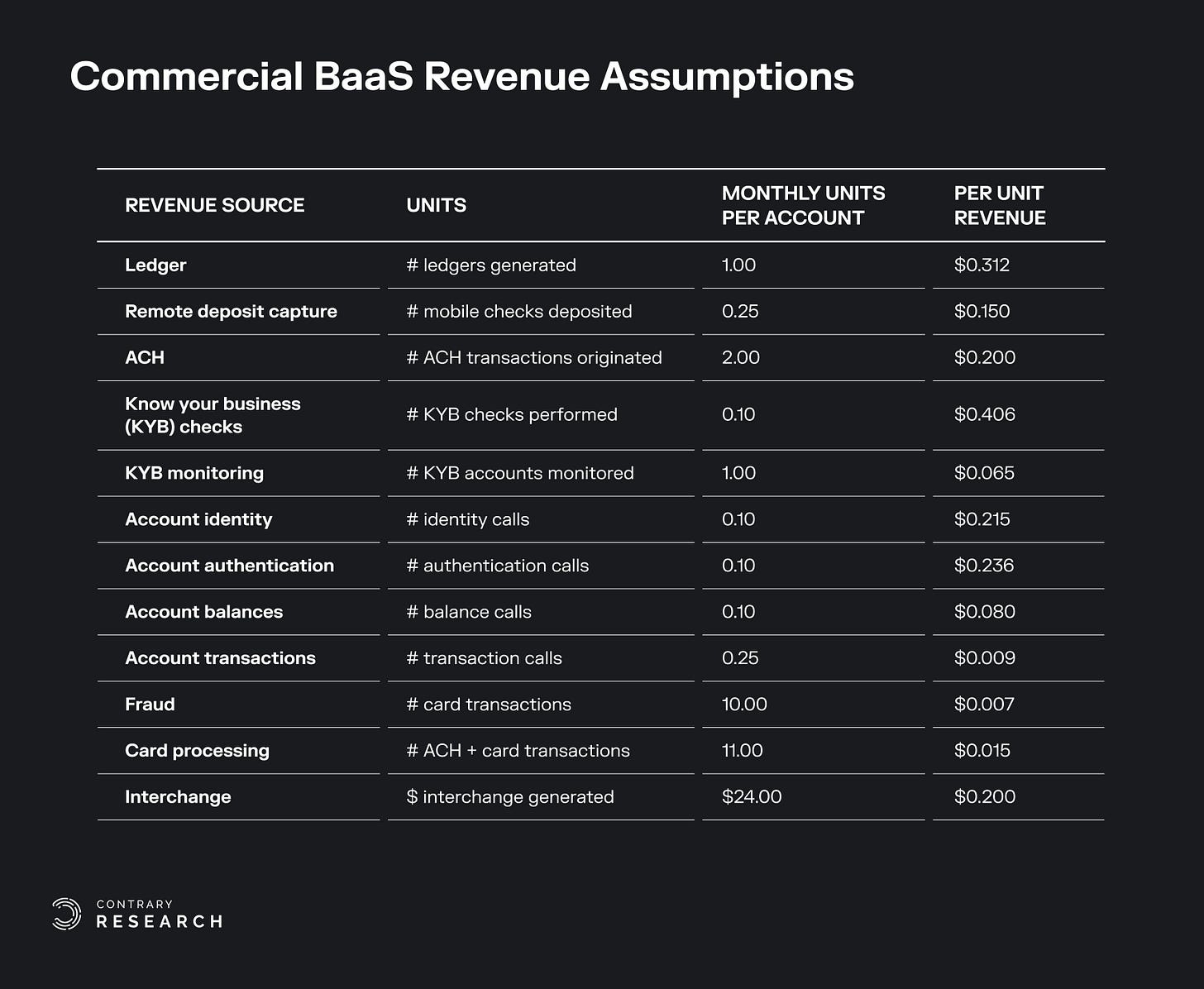

By acting as card issuers, BaaS banks receive a cut of interchange from the merchant’s bank on every transaction. While the amount of interchange varies between banks, according to Synctera, non-bank companies typically receive 70% in BaaS partnerships, while the BaaS provider and partner bank share the remaining 30%. In an interview with Contrary Research, one founder of a prominent BaaS provider stated that they have even seen some non-bank companies receive up to 90% of the interchange revenue due to their scale. Alongside interchange, sponsor banks have several other potential revenue streams. For example, banks providing commercial accounts could generate revenue through KYB checks and monitoring, fraud detection, account authentication, etc.

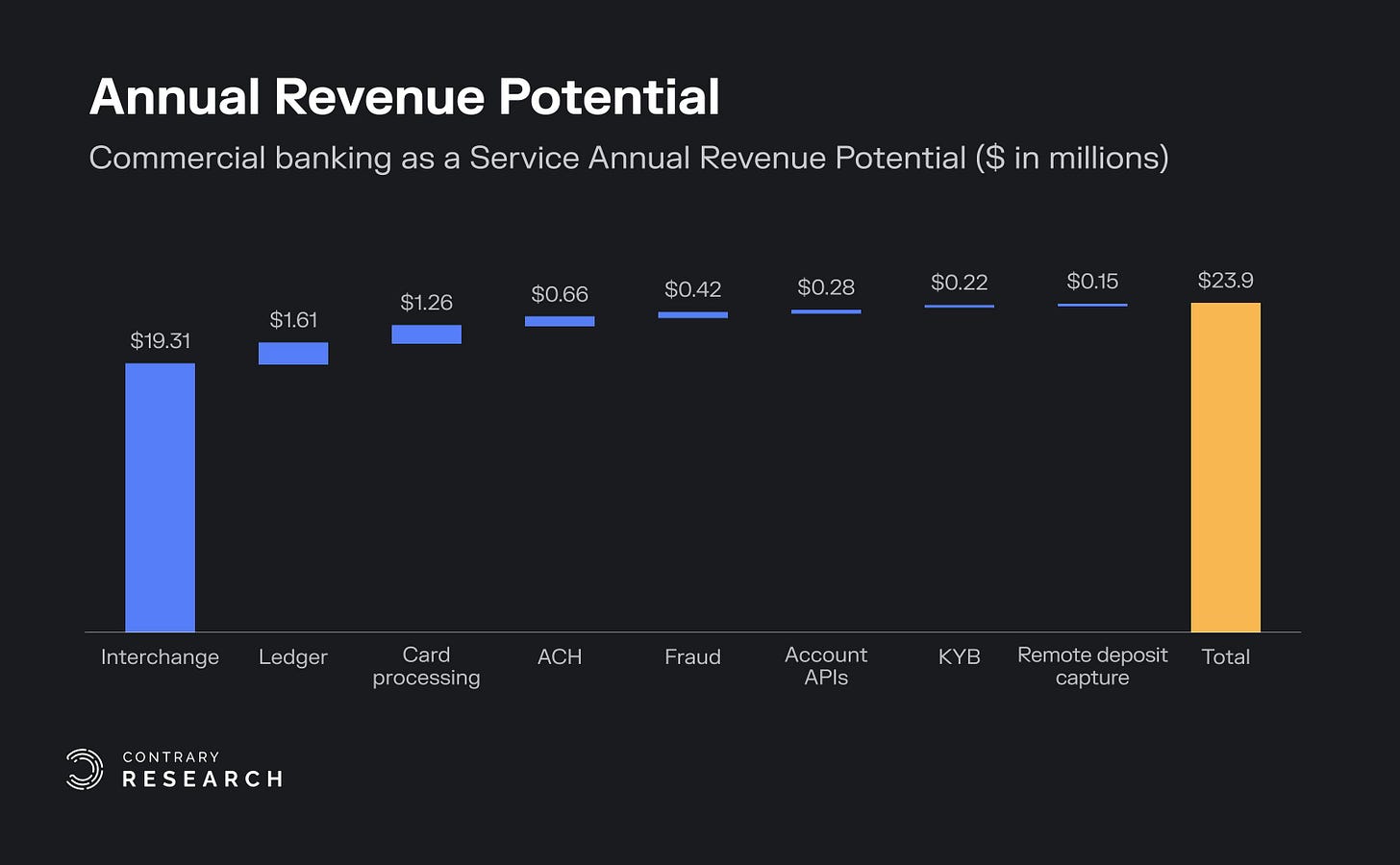

Many of these prices can differ significantly depending on a business's scale or pricing structure. As modeled by Cornerstone Advisors, with these commercial BaaS revenue assumptions, a monthly growth rate of 2%, and 300K commercial accounts, a typical sponsor bank could generate roughly $24 million in annual revenue from BaaS alone.

That’s a meaningful lift for a typical community bank. In 2023, US community banks generated a total net income of ~$26.8 billion and there were ~4K community banks. That means the average community bank generated ~$6.7 million in annual income in 2023. In 2022, Coastal Financial Corp generated 49% of its total net income from BaaS alone. Therefore, with 300 community banks projected to offer BaaS in 2026, BaaS revenue is expected to reach $25.5 billion by 2026.

Further, many of the benefits that community banks receive from engaging in BaaS arise from second-order effects unrelated to interchange. While most community banks have struggled to attract deposits due to consolidation among national banks like Chase, partnering with non-bank companies that are national in their marketing allows these community banks to gain national reach. This means that they can compete on a national scale.

As a result, community banks across the US are considering whether to engage in partnerships with fintechs and non-bank companies by adding BaaS to their core offering. In a 2022 report, 85% of banking executives stated that they were already implementing or planning to implement BaaS solutions. Since the release of that report, BaaS deployments have jumped globally by 37%.

But despite the growing interest in BaaS, partnering with non-bank companies is inherently risky. Financial services is one of the most highly regulated industries in the US. Therefore, as the number of community banks involved in BaaS increases, the need for solutions that reduce the complexity of launching a financial product while also maintaining compliance at scale via technology is increasing.

Unfortunately, these two goals can potentially be contradictory. Launching a financial product as efficiently as possible means both the fintech and the partner bank want to operate at maximum speed with minimal friction. But minimal friction also means minimal oversight, and that leads to significant compliance risk.

Addressing the opportunities and risks in the BaaS space has resulted in the emergence of several different approaches and categories:

(1) Traditional community banks

(2) Middleware providers

(3) Bank marketplaces

(4) BaaS-first banks.

Traditional Community Banks

Traditional community banks are banks with less than $10 billion in assets that are engaging in BaaS, yet have not historically been tech-first banks. These banks often engage in BaaS in two ways: they either partner with fintechs and non-bank companies via a BaaS provider, or they partner with them directly. As of March 2024, the majority of these banks are taking a hybrid approach, bringing in customers via BaaS providers and direct relationships.

Since many traditional community banks have recently layered on a BaaS strategy, they typically do not have the technical stack or team to compete with other players in the space. As a result, they tend to focus on competing by winning customers operating in specialized use cases that have specific risk profiles.

Community banks have often been at the center of regulatory problems through their partnerships with middleware providers in BaaS. Since community banks are not tech-first, they have mainly relied on middleware BaaS providers to bring in customers for deposit growth, but this reliance has come at a compliance cost, with many traditional community banks receiving consent orders, which are “binding legal orders issued by financial regulators that force receiving institutions to formally address significant violations of regulatory standards.”

Not only do traditional community banks often struggle with weak technical stacks, but the risks for non-bank companies to engage in a direct partnership with only one partner bank can drive potential customers to seek alternative solutions. As we saw over the course of 2023, different regulatory environments and leadership changes can result in community banks scaling back their efforts in BaaS.

As a result, it’s risky for end customers to be reliant on one bank to power their financial products. While such risks apply for all models in BaaS, direct partnerships with traditional community banks are particularly vulnerable as the process for a non-bank company to directly connect with another partner bank is both costly and time-intensive. In an interview with Contrary Research, Sheel Mohnot of Better Tomorrow Ventures described the risk this way:

“Operating with a single direct partnership is risky. You don’t want to end up in a situation… where you're dependent on one bank and then get off-boarded and ultimately go out of business.”

Further, since specific banks have different product portfolios and specializations, if a non-bank customer scales its programs and wants to launch new financial products that its existing partner doesn’t support, it may need to build an entirely new relationship with a different partner bank. In an interview with Contrary Research, Peter Hazlehurst, co-founder of Synctera, discussed this problem:

“Banks becoming their own providers is not a great solution because each bank has different APIs and systems. As a company, if you want to have 2-3 relationships to scale across capacity, then you’re not going to want to embed 2-3 different banking APIs under the hood. It’s too much hassle and takes too long.”

Sheel Mohnot also added:

“How much work do you want to do and how much control do you want to have? With going directly to a legacy bank, you’re doing a lot of stuff that you have to figure out all by yourself. In fintech, there are a million edge cases to build for. This model only makes sense if you have a really large team dedicated to it and, even then, things will still break.”

Given the challenges and associated risks of non-bank customers engaging in direct partnerships with traditional community banks, many believe that this model will not emerge as the dominant one in BaaS over the next several years. With that said, traditional community banks will still play a critical role in partnering with non-bank companies through BaaS providers that have a network of banks that companies can more easily switch between.

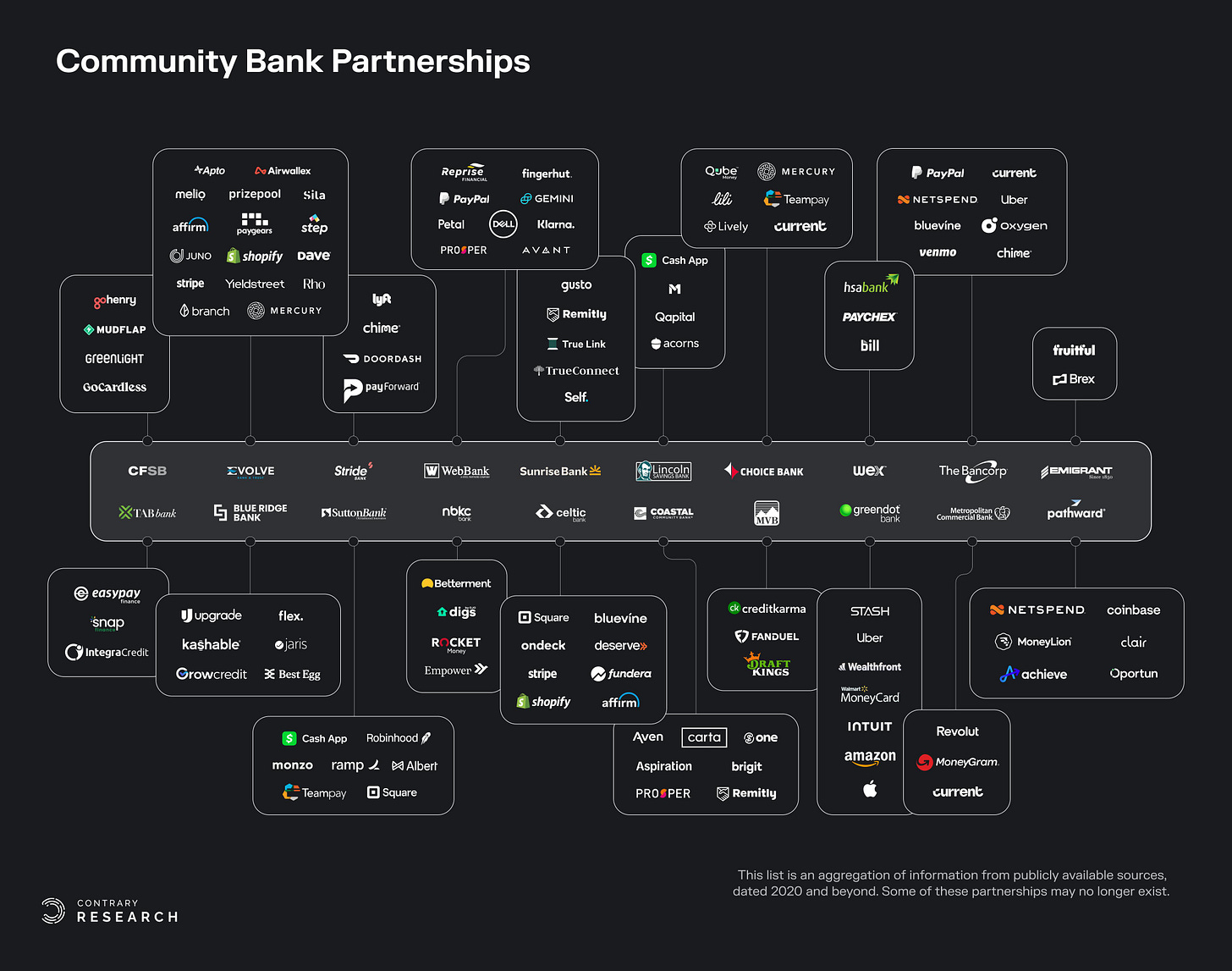

Below is an overview of select community bank partnerships. Some of these companies work directly with the community banks, while others connect via a BaaS provider. Certain banks, specifically Column, Lead Bank, and Cross River Bank were excluded as they fall under a distinct category of BaaS-first banks. We define BaaS-first banks as tech-native banks that have built out the required technology stack to offer a direct BaaS program and have large engineering teams. Most partner banks are not BaaS-first banks as they are not tech-native.

Middleware Providers

Middleware providers are BaaS companies that build technology and, combined with a network of banks and non-bank companies, act as an abstraction layer between a partner bank and a non-bank company. In this model, speed is the priority. Onboarding is fast, compliance is abstracted away, and there is not a direct relationship between the partner bank and non-bank company.

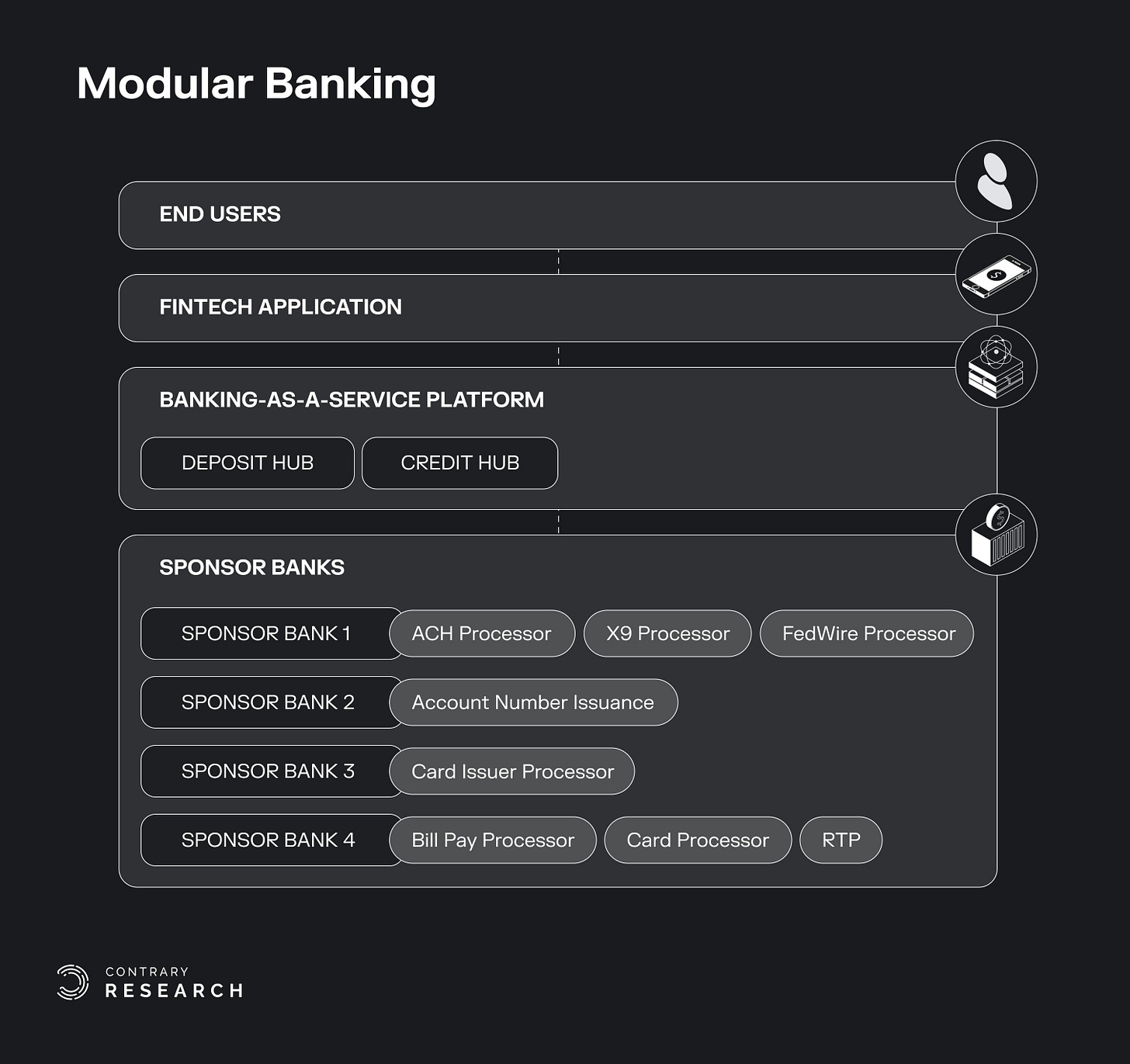

Occasionally, non-bank customers initially operate as “tester programs” with these middleware providers, meaning that they aren’t introduced to the partner banks storing their customer deposits until they have matured. In this model, a non-bank customer of a middleware provider can often have multiple banking products (payment processing, FBO accounts, and issuing) divided between different partner banks. The resulting model ends up being more modular and stacked.

While this modular banking framework is a common marketing tool for middleware providers, many other fintech founders criticize this model, with one founder we talked to describing it as “interesting in theory, but not how it works in the real world.”

Several BaaS providers began in this category, but middleware providers have been the subject of many of the regulatory issues in BaaS. In an interview with Contrary Research, Eric Kaplan, of Bessemer Venture Partners, broke down why this model has experienced fundamental challenges:

“Building valuable infrastructure in fintech takes a long time. Usually, moving too fast is not a good sign. Some BaaS providers moved too fast onboarding customers while banks never developed a direct relationship with these customers. The result: partner banks got in trouble for not having proper oversight of these new customers.”

In many cases, the middleware model has resulted in a compliance nightmare for banks and non-bank companies alike. Some non-bank companies never instated a contractual agreement with a partner bank and solely worked through the BaaS provider. While this optimized their time to market, it was anything but compliant.

Many middleware providers tend to market compliance as a bundled offering, absorbing compliance responsibilities and relying on internal teams to review any workflows related to compliance. However, outsourcing compliance to middleware providers can lead to numerous issues. For example, if a customer is flagged during KYC checks, a non-bank customer has no (or limited) visibility into why that customer was flagged and whether that flag was merited. Yet non-bank companies are typically the party with the most context on the potential customer. This can lead to a poor onboarding experience for potential customers, meaning that the non-bank’s end-user experience and approval time are entirely dependent on its respective middleware provider.

Middleware providers and their non-bank customers also often treat their relationship with banking providers as a light switch, thinking they can pick and choose banks to work with and then turn them on and off as needed. But in reality, BaaS is built around partnerships. Partner banks have teams performing real compliance oversight on behalf of customers, but in many cases that effort has been abstracted away by the middleware provider. Tim O’Shea at the Klaros Group believes that partnerships require defining each party’s responsibilities and ensuring they perform to the bank’s standards. In an interview with Contrary Research, he described it this way:

“Some institutions have struggled to fully define risks, especially where the bank customer is a fintech supporting retail end users. That disaggregation requires clearly defined responsibilities throughout the value chain. Lack of visibility and true partnership open the door for regulatory problems, including consent orders.”

Beyond communication and compliance issues, the middleware model also suffers from graduation risk. As non-bank customers scale, they naturally want to integrate with other financial products, which require a direct relationship with a bank. However, middleware BaaS providers act as an API with partner banks. Anything more complex requires the non-bank customer to build complex underlying core systems. Ahon Sarkar describes the challenges with not rebuilding core infrastructure this way:

“The problem with not rebuilding the core is, it’s like taking a Fiat 500 and taking out the body and then putting a Ferrari body on top. It’s still a Fiat 500 underneath. The approach allowed people to launch products quickly, but the moment you needed to actually access the real core, you couldn’t do that. Ultimately, it’s a wrapper around the traditional business.”

As a result, some of the largest non-bank customers, including Mercury, have left their BaaS middleware provider and chosen to engage in a direct relationship with an issuer processor (Lithic) and partner banks.

Further, beyond requiring direct relationships to build certain products, the middleware model is flawed due to a delay in reconciliation between a bank’s core system and a BaaS provider’s system. Since data is transmitted at the end of each day between the two systems, reconciliation errors can, and have, emerged. Ahon Sarkar went on to explain how this can also lead to the mishandling of customer funds:

“In many cases, consumer accounts from the BaaS provider are set up in the bank in what’s called an FBO account, as opposed to real bank accounts for real people. They create one big bank account for the client and they just subledger all the individual customers underneath. So from the bank’s perspective, they’re seeing one big $50 million account, not 500,000 customers with different balances.”

This lack of visibility can have important consequences. In 2022, the relationship between Synapse (a BaaS middleware provider) and Evolve Bank & Trust (a partner bank) broke down, in part due to $13 million in missing customer funds that each party blamed the other one for. Fintech Business Weekly obtained an email sent from Evolve to Synapse highlighting the magnitude of the issue:

“The balances tend to differ a couple hundred million on the daily. I am comparing the Synapse data to the FBO for consumer and business users.”

The mishandling of customer funds between Synapse and Evolve emphasized the importance of banks and non-bank companies building a strong relationship with each other. As Jackie Reses, CEO of Lead Bank, described in an interview with Contrary Research:

“Many companies working with an aggregation layer don’t know much about the compliance needs of the underlying bank. It is paramount for a company to do due diligence on their underlying bank partner and test for compliance capabilities, risk aperture and financial strength beyond the core technical and product competency. You need to understand this layer of your infrastructure so that it doesn't present an unexpected risk to your business.”

Given the issues with the middleware model, many believe it may no longer exist in ten years. In 2024 and beyond, banks will need to have some form of direct connection with non-bank customers, and a full abstraction of compliance is simply not sustainable. Regulators have made this increasingly clear.

However, while middleware may cease to exist in the near future, many of the companies that have traditionally operated as middleware, such as Synapse, Solid, Bond, and others, can continue to play a key role in the BaaS ecosystem if they modify their approach. In fact, we’re already witnessing this shift in approach take place. In an interview with Contrary Research, Sankaet Pathak, co-founder of Synapse, observed that:

“We are in the early stages of the market. We’ve learned that as customers grow, they prefer, not necessarily for economic reasons, to have a direct partnership with a partner bank. This requires changing your engagement model so that customers and banks have more interaction. That’s something we have done and are continuing to do.”

Bank Marketplaces

Bank marketplaces are BaaS providers that enable direct partnerships between multiple partner banks and non-bank companies via a marketplace. These providers typically build the tech stack to enable these partnerships by making it easy for both parties to connect.

Bank marketplaces emphasize the importance of direct connections between partner banks and non-bank companies for compliance purposes. As a result, they have largely avoided the majority of regulatory issues that have plagued other BaaS models. By facilitating direct relationships between banks and non-bank companies, partner banks have greater oversight and visibility into the operations of their end customers, leading to a compliance-first approach.

Another key characteristic of the bank marketplace model is that the majority of providers have adopted a multi-bank model where non-bank companies can directly connect and, most importantly, switch from one bank to another using the same APIs. As discussed earlier, being entirely dependent on one bank creates risk for non-bank companies. Bank marketplaces minimize this risk by enabling non-bank companies to switch banking relationships as needed. As described by Sheetal Parikh, associate general counsel at Treasury Prime:

“Without any other bank partners there is never the option of portability to the extent a fintech outgrows its bank partners for any reason. Leveraging Treasury Prime’s multi-bank network, we are able to — and we have — taken a fintech from one bank to another bank in certain instances. With our model, fintechs don’t face the risk of over-concentration or dependency because there are always other bank options to consider.”

This multibank model also benefits the partner banks on the other side of the equation. In an interview with Contrary Research, Chris Dean, co-founder and CEO of Treasury Prime, discussed these benefits:

“At our core, we are a software vendor that goes to banks and lets them join a ‘marketplace’ to interact with fintechs as they see fit. If they want a 1 on 1 relationship, they can do that. If they want to partake in a really large deal across 3-4 banks, they can do that too. They can have big or little deals, but in all those cases they’ll use our software to run those relationships, but they will run compliance.”

Further, given the contagion risk that exists in BaaS, if a single bank receives a consent order, the non-bank company that partnered with them will be affected, even if their program is fully compliant. As a result, in an environment of increased regulatory scrutiny, many investors, like Sheel Mohnot, believe that multi-banking partnerships are key to minimizing these risks:

“Unit has a dozen banking partners and none of the consent orders had anything to do with any of the programs on Unit. There were issues with those banks that had nothing to do with programs on Unit. In BaaS, you end up getting penalized for stuff that’s outside the scope of your work. That’s why we strongly believe that direct multi-bank partnerships will be the way forward.”

Yet, multibank partnerships aren’t the only way of mitigating contagion risk. In an interview with Contrary Research, William Hockey, CEO of Column (a BaaS-first bank), described his approach this way:

“Contagion risk is one of the key considerations for our onboarding. Will this prospective client do something that may impact our other clients? If the answer is not a 100% 'no' then we will not onboard them.”

In terms of competitive positioning, the three key players within this segment, Treasury Prime, Synctera, and Unit, vary in their involvement with both partner banks and non-bank companies.

Treasury Prime: Treasury Prime works more closely with partner banks than with non-bank companies, essentially providing banks with a tech stack to work with end customers. As a result, Treasury Prime can enable direct deals to happen between banks because it has built a program around key components like network transfers and instant money movement. An important differentiating factor of Treasury Prime’s marketplace compared to some others in the category is that competition exists amongst buyers and sellers, akin to a true network. As a result, Treasury Prime does not decide which fintech and banks work together, but solely provides the underlying technology to facilitate the relationship.

In February 2024, Treasury Prime announced that it was shifting its focus entirely to a “Bank-Direct” model. While the change saw Treasury Prime eliminate its focus on identifying fintechs to partner up with banks, its core offering of providing software to partner banks to facilitate direct partnerships with fintechs remains unchanged.

Unlike some competitors, with Treasury Prime, non-bank companies work to set up their own compliance program via integrations with 3rd party providers including Alloy, Unit21, and Cable. In other words, Treasury Prime offers help with a compliance solution, but it is ultimately owned by the partner bank and the non-bank company. Since non-bank companies cannot offload compliance to Treasury Prime, this approach takes on the least risk within this category from a compliance perspective. However, it may have less appeal to earlier-stage non-bank companies as there is more required of them on the compliance side. Eric Kaplan, at Bessemer Venture Partners, described the strategy this way in an interview with Contrary Research:

“If you are an intermediary player like Treasury Prime, you’re more of a matching service. That means you’re not taking on much of the risk and so a lot of the regulatory scrutiny from the OCC won’t concern you. The tradeoff is that the depth of services you can offer companies is more limited.”

Synctera: Synctera sits between banks and non-bank companies. It not only helps the two sides meet but also facilitates the relationship on both sides. A non-bank company will approach Synctera and Synctera will evaluate it based on funding, compliance, and several other factors. Based on that review, Synctera may then decide to present the opportunity to all of its partner banks. Typically, Synctera will connect the non-bank company with 3+ banks, and then the non-bank company will work with the bank(s) that they are most strategically aligned with. Peter Hazlehurst, co-founder of Synctera, described the process this way in an interview with Contrary Research:

“We’ll say to companies: here are two offers with different pricing considerations, different compliance considerations, and different timing considerations. For example, say you are trying to launch international banking with remittances. One bank says they'll bank you even though you're doing remittances with a vendor such as Wise, but it's going to be really expensive on KYC. Another bank says they’ll support you building home grown remittances, but it’ll take a long time in terms of compliance to build out the program. Which bank works best for you? Do you want to launch quickly but have a more constrained solution, or do you want to build a more expansive program that’s more flexible and launch in six months?”

In terms of competitive positioning, Synctera often wins customers due to its focus on specialized use cases. As Hazlehurst explained:

“When we win, we win for different reasons. If the customer is sophisticated and wants to do lots of interesting things that are unique and specialized, we tend to win in those scenarios. We’ve built out specializations for international money movement, banking foreign nationals, and in niche industries like cannabis banking.”

Unit: While Unit was initially more of a middleware player, in 2024, it is now positioned as a technology and managed-services provider to banks. It provides an operating system – including ledgering, oversight dashboard, reporting, and data access – to help banks launch and manage direct banking programs. In an interview with Contrary Research, Itai Damti, co-founder of Unit, described his company’s approach this way:

“We are a technology layer that allows bank and fintech companies to come into direct, ongoing relationships. The banks we partner with think of Unit as an operating system to help them manage and oversee their direct program relationships. Non-bank customers meet banks and engage in a direct contractual and operational relationship, supported by our platform. We facilitate this through technology and managed services.”

In an interview with Contrary Research, Amit Kumar, a partner at Accel who sits on the board of Unit, described the nuance of Unit’s approach as follows:

“Within this segment, there are different approaches. Some folks like Treasury Prime decided they wanted to sell software to partner banks. [Unit's] focus is on creating simplicity and standardization - for both the bank and the non-bank - making it easier for banks to provide direct oversight over the non-bank customer. As a customer, you need to have a lot of sophistication to stand up these programs – that’s one of the reasons the market has stayed relatively small. What Unit is doing is lowering the friction that it takes to successfully stand up and manage one of these programs."

The key challenge that all three of these bank marketplace companies face is that, on the surface, it appears easier for non-bank companies to work with middleware providers instead of with the bank marketplaces outlined above. With middleware providers, non-bank companies don’t have to develop a direct relationship with partner banks, and most of the heavy lifting is already done for them. However, this comes at a heavy compliance cost.

In an interview with Contrary Research, Amias Gerety, partner at QED Investors, described a narrative shift that is needed to emphasize the importance of optimizing for compliance-first relationships over time to market:

“Too many people think of this model as disintermediation. But, in reality, that’s not true. This model is software-based intermediation. BaaS is designed to make it easy for fintechs and banks to connect, not to sever the need. Under all circumstances, you need a direct relationship with a bank, and those partnerships require intermediation, not disintermediation. People say no to Treasury Prime because it seems easier to work with middleware providers. That means you’ll never learn how to work with a bank and if something goes wrong, you’ll be fired. Banking isn’t easy. If you want to be in finance, you have to be in finance.”

Overall, within the BaaS sector, the bank marketplace model is well-positioned to power the future of embedded finance. Banks and non-bank companies need to have direct relationships, but non-bank companies also need access to multiple partners to de-risk their products in many cases. This model enables both and also provides the underlying technology to make the relationship smooth.

However, important challenges remain. Many early-stage companies don’t understand the significance of compliance. As a result, the BaaS players in this segment must continue to effectively communicate the importance of direct partnerships. Further, the market is currently unbalanced – there exist many more non-bank companies than banking partners can support. This is a supply-side marketplace challenge that will need to be solved via new entrants and technology that streamlines and standardizes oversight for large fintech programs.

BaaS-First Banks

BaaS-first banks are tech-native community banks that have built out the required technology stack to offer a BaaS program. These banks work directly with fintechs and prioritize BaaS as their core growth strategy. Given their nature as banks, these players have three primary objectives: (1) build a tech stack that enables non-banks to move quickly, (2) ensure all their programs are compliant, and (3) maintain a strong balance sheet.

From the non-bank perspective, working directly with BaaS-first banks offers a larger slice of interchange and greater product flexibility without the tradeoff of compromising on speed or the smoothness of technical integrations.

It is important to note that there exist very few players in this segment due to the difficult nature of attaining a bank license. Most founders don’t have the financial backing to acquire a bank, and thus the number of players operating this model is very limited. In fact, two of the most well-known players – Lead Bank and Column – were both built or acquired by fintech veterans who invested tens of millions of dollars in their respective companies. Because of this, some observers don’t expect to see many more new BaaS-first banks emerge without changes in both the presidential administration and in FED personnel. In an interview with Contrary Research, one BaaS founder described the current regulatory climate this way:

“Increase tried to buy a bank and got rejected and shut down. The founders’ background is somewhat similar to Jackie’s [CEO of Lead Bank] and William’s [CEO of Column]. The biggest difference is that he tried to buy a bank during a different regulatory regime than [Lead and Column] did. I’d say that if Biden gets elected again, the door to the BaaS-first bank model is closed. The likelihood someone would be able to pull off what Jackie and William did is close to zero.”

This means, among other things, that since very few BaaS-first banks currently exist and the barriers to new ones emerging are high, the number of customers this category can support may be limited. However, when asked about this challenge, Column CEO Hockey took the opposite view:

“We don’t set limits or caps on our client count. Our onboarding pace is the result of who we choose to work with, which is driven by the risk reward analysis of each prospective client in our pipeline. Some of the largest fintechs in the ecosystem today trust us to be a compliant and steady partner and we take that very seriously. This means the goal is never to “hit a number” but rather to grow responsibly.”

Some of the limitations may be more a function of BaaS-first banks’ preferences than a limitation on their capabilities to serve more customers. When asked about this topic during an interview with Contrary Research, Jackie Reses, CEO of Lead Bank, said that:

“We don't have sales or marketing functions as all the companies that we work with come from our own network. We select clients based on the quality of the product, team, and compliance orientation. I also send a lot of companies to others such as Unit, Bond and Treasury Prime.”

In addition to any natural self-imposed scale constraints, BaaS-first banks face the same challenge as traditional community banks – certain non-bank companies want to work with multiple banking partners, and, in this model, that requires multiple integrations with different banking systems.

It is important to note that while some believe that working with multiple banks is necessary to prevent risk, others believe that multibank partnerships are only useful for certain financial products. As Hockey put it:

“There are definitely situations where a multibank strategy is prudent. Credit origination programs – given the structuring, capital, and traditionally lighter integrations – allow for more straightforward multibank setups. However, working with multiple banks for the same payments, deposit accounts and card offerings adds significant technical and operational complexity and confusing user experience - for everyone except the largest programs it’s usually not worth it. Some people think that multiple banks will give them more regulatory resilience, however, in reality the operational complexity ends up adding more regulatory exposure.”

In terms of competitive differentiation, the banks in this category generally exist on a spectrum. While some banks opt to support more technical products that are lower risk, such as deposits, others instead opt to support products that are higher risk, such as consumer loan origination, but require less technical depth.

Overall, despite some of the challenges and lack of supply of BaaS-first banks, the BaaS-first bank model represents an attractive solution for BaaS: a tech-first, fintech-friendly model built directly by a bank with a charter. Ideally, the integrations are smooth and the compliance is more ensured. There are also no middlemen, so the direct line of communication ensures stronger alignment between both parties. Granted, no model will be immune from compliance and regulatory friction.

Given this, some of the largest fintech and non-bank companies are switching to this model in order to take advantage of the unique blend of tech-first capabilities and low compliance risk that it offers. The technical expertise that BaaS-first banks have makes the integration process easy for engineers at non-bank companies. Further, by having direct access to the BaaS-first bank, non-bank companies can work with them to build tailor-made solutions, making this model particularly attractive to large customers with complex products.

The Uphill Battle For Banking Infrastructure

Regulatory Struggles

In 2020, as a new presidential administration took office in the US, the regulatory landscape in BaaS shifted entirely. Suddenly, every partner bank in the space was exposed to regulatory pressure, with many banks receiving consent orders due to their mismanagement of the BaaS programs they supported. While some in the industry believe the OCC has taken its regulatory scrutiny a step too far, many people, including Jackie Reses and William Hockey, believe that it is not only justified by also a net positive for the space in the long term. In an interview with Contrary Research, Reses described it this way:

“Additional regulatory scrutiny will continue and in many cases it will improve the industry's controls. When regulators ask questions about KYC, customer support, underwriting,and servicing, many banks can’t answer these questions because they don’t know how to articulate their customer’s products well. Some banks who got into this business are now out over their skis in terms of their understanding of what they actually have on their rails.”

In an interview with Contrary Research, Itai Damti, co-founder of Unit, shared a similar sentiment:

“I expect to see more regulatory attention on the ecosystem. In fact, I believe scrutiny is an excellent thing for our industry – it makes our ecosystem better. Although the sector would benefit from clearer guidance as to regulatory expectations around third-party partnerships, best practices are starting to emerge which is a positive development.”

One of the reasons traditional community banks have received consent orders is due to their relationship dynamics with non-bank companies. Community banks have been struggling over the last decade with falling net interest margins and a consolidation of deposits amongst large banks. Partnering with fintechs and non-bank companies has been a lifeline.

But because non-bank companies and BaaS providers directly generate revenue for their bank partners, they hold leverage. Community banks are therefore directly competing to work with certain companies, and this can lead to banks deprioritizing compliance in order to win customers. Further, since many community banks work with non-bank companies through middleware providers that abstract the entire relationship, the lack of visibility in some of the BaaS models only accentuates this issue.

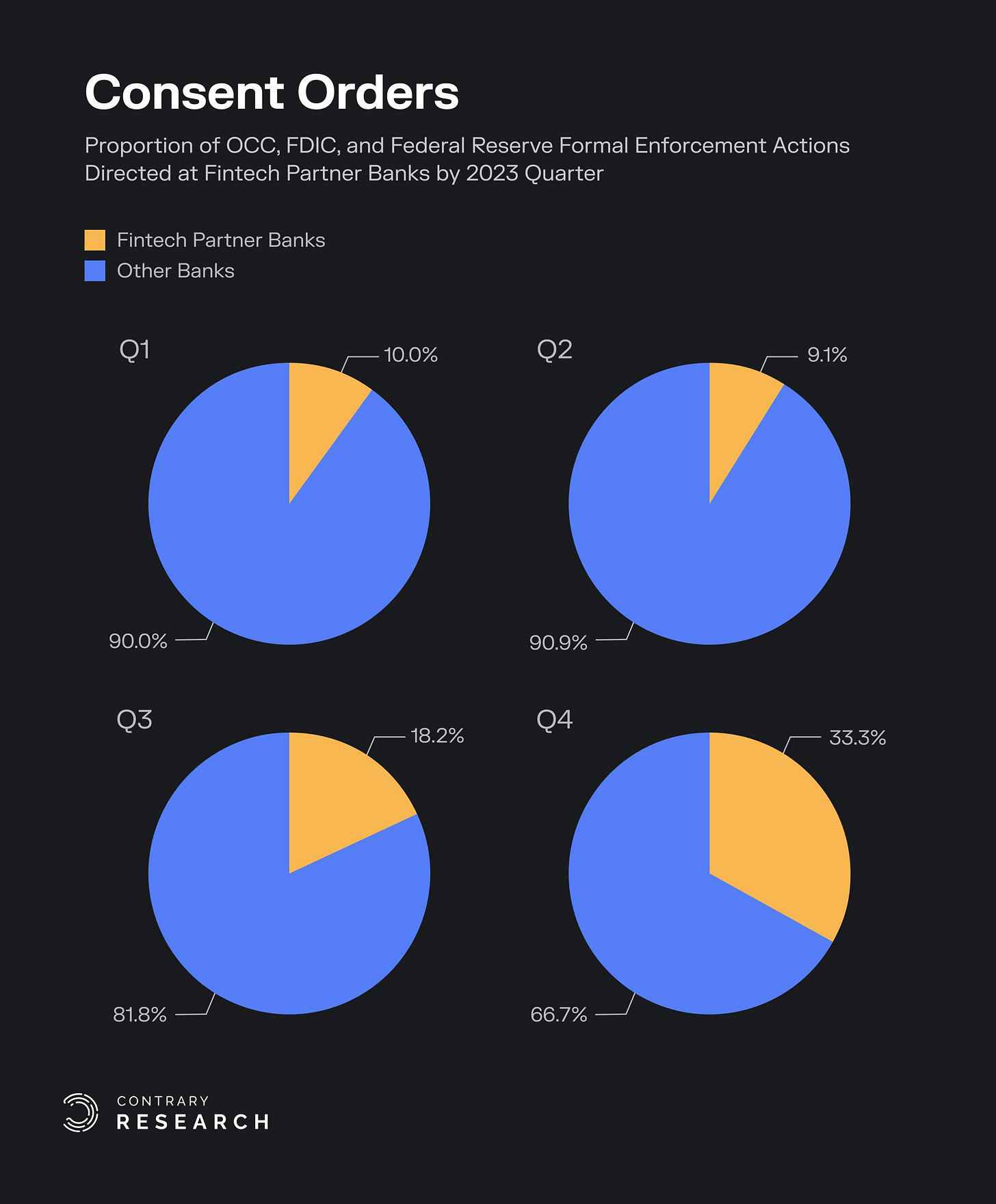

This unbalanced relationship is what’s driving consent orders. In 2023, banks that enabled BaaS programs with fintechs and non-bank companies “accounted for 13.5% of severe enforcement actions issued by federal bank regulators, including prompt corrective action directives, cease and desist orders, consent orders, and formal agreements.” To put this in context, there were ~120 community banks in the US that support BaaS and 4.7K general FDIC-insured banks as of 2023. This means that BaaS-supporting community banks comprise 2.5% of total US banks, but account for 13.5% of severe enforcement actions.

And, this is just the tip of the iceberg. In an interview with Contrary Research, Jonah Crane, partner at Klaros Group, explained:

“Lots of these banks are also facing internal reviews and informal actions that aren’t public knowledge. I think we will continue to see more and more consent orders until the industry has proper guidance.”

While certain models reduce the impact of consent orders, such as the multi-bank model, it has become increasingly clear that no matter what segment of BaaS you operate in, and even if you are fully compliant, you are liable to be impacted by consent orders. In an interview with Contrary Research, Sankaet Pathak, co-founder of Synapse, described it this way:

“Right now, regulatory scrutiny is the hardest thing facing everyone in our industry. Some banks will inevitably leave the space – it is painful to be doing this. I believe the scrutiny is too heightened; some consent orders are for good reasons but there are also some that are overheightened. Lots of these consent orders aren’t actually regulatory breaches.”

Some partner banks are also scaling back their involvement in BaaS due to regulatory concerns. For example, Blue Ridge Bank, a prominent BaaS community bank, announced that it was offboarding dozens of fintech partners in order to regain favor from regulators following its consent order in 2022.

This shift is also being captured in the data: one report found that out of 122 C-level bank executives, those who said that working with fintechs was an integral part of their strategy fell from 43% to 39% between 2022 and 2023.

However, others believe that the number of partner banks won’t decrease, but that the bar will just be raised. In an interview with Contrary Research, Chris Dean, co-founder and CEO of Treasury Prime, discussed what he was seeing in the market:

“There is definitely more friction in the market now, but there is not a decrease in banks' interest in working with fintechs. They just want to be careful and won’t engage in risk that they don’t think is worth it. Over the last year, they’ve been increasingly emphasizing investment into compliance tools.”

This is directly impacting early-stage non-bank companies looking for a BaaS provider. As banks are now seeking more mature customers, it can be hard for early-stage customers to find a partner willing to work with them. In fact, Peter Hazlehurst, co-founder of Synctera, shared how this was already beginning to take shape:

“It’s partly driven by our own selection bias, but the minimum bar for a startup to work with us has risen quite significantly. We used to work with pre-seed companies who wanted to test out products, but now the bar is normally around $5 million in funding. This isn’t to say great founders can’t find a home, but overall the market is moving to more mature and scaled opportunities because the cost to onboard is roughly the same for a big versus small client. The banks are also realizing they only have so many opportunities each month to onboard customers, so they prefer to focus on established customers since the cost of onboarding doesn’t change.”

Overall, regulatory struggles are expected to continue until community banks and middleware BaaS providers shift to a compliance-first mindset with a strong focus on direct relationships. Until that happens, more consent orders are likely, and some banks will exit the space entirely, but the end result will be a fitter industry with stronger relationships.

Rising Compliance Costs

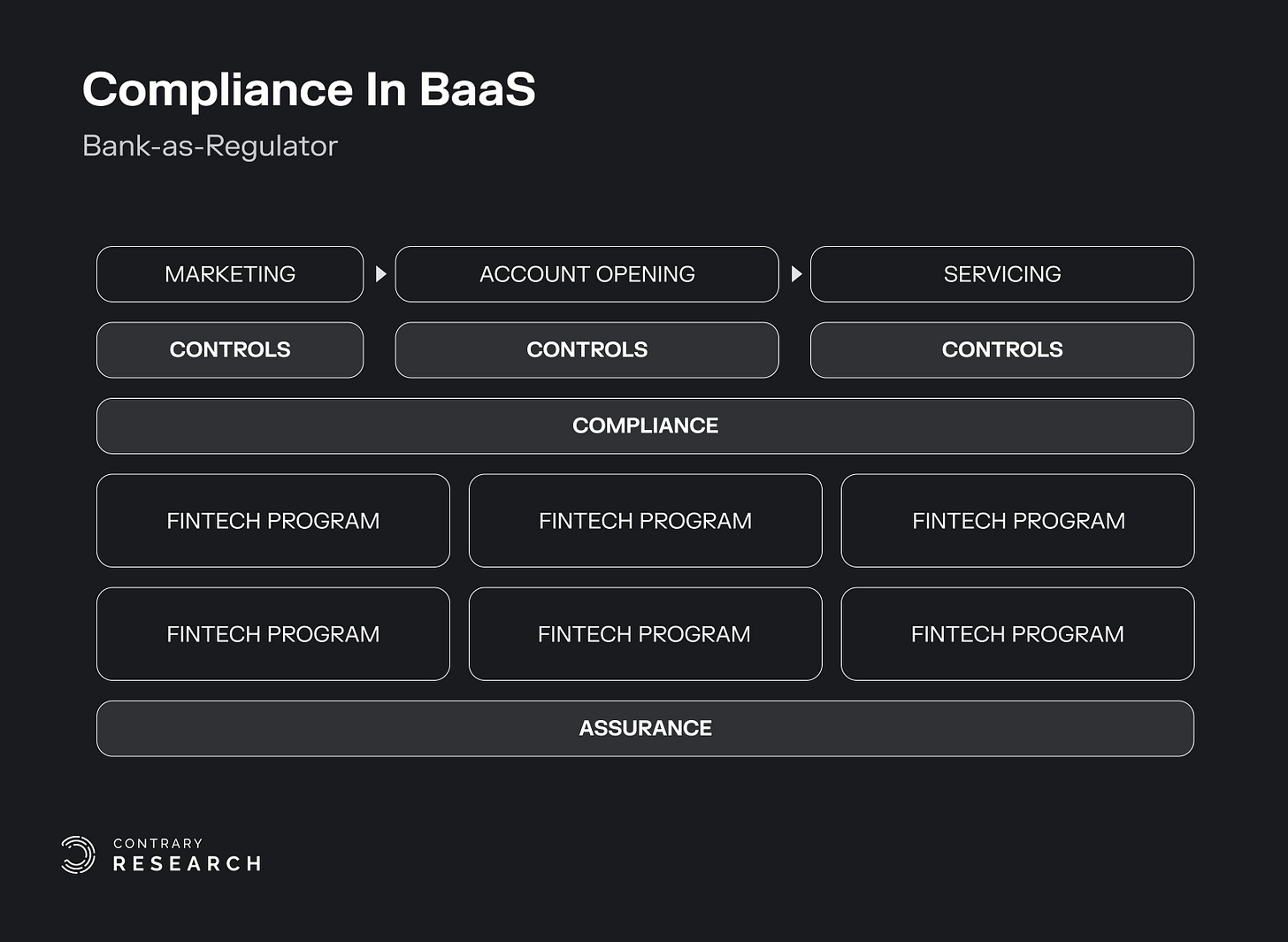

Regardless of what operating model is used, the liability of compliance in BaaS ultimately falls upon partner banks. So, with an increasing number of consent orders, many banks are increasing their investment in compliance tooling and personnel. The reason? Existing compliance models are not purpose-built for BaaS.

Traditionally, if a community bank wants to open a branch, it simply extends its already operating compliance infrastructure – new frontline employees are trained on existing policies, the same account onboarding system is used, and transaction monitoring doesn’t change either.

But, as fintech writer Alex Johnson has noted, if expansion via traditional methods equates to opening one physical branch, expansion via BaaS equates to opening 10-20 abstracted branches within 1-2 years. The core difference isn’t just the number of branches, but also the people running them. With abstracted branches, non-bank companies and BaaS providers (who are also VC-backed, growth-focused companies) are in charge of risk and compliance. Their incentives are entirely different, and on top of that, each branch also has its own branding and specialized products, complicating the process of ensuring compliance.

As a result, the industry has been searching for a new compliance structure for BaaS. While different banks have opted for different models, the prominent model that is emerging is the one where the bank acts as a regulator.

In the regulator model, a partner bank directly oversees all its partnerships, but over time, allows non-bank companies and fintechs to take on some of the risk management and compliance work. As a result, the costs of compliance are slowly being offboarded to the non-bank companies.

With an increasing number of consent orders, many banks are also increasing the requirement for what it actually means to “take on” front-and-second-line compliance. As discussed by William Hockey, CEO of Column, in a February 2024 interview with Contrary Research:

“Regulatory expectations are ballooning, as they should, and we are seeing many unprepared banks and fintechs forced to adapt fast. This often means fundamentally changing the way these partnerships are operated, bringing in experienced personnel, and re-architecting the compliance requirements and technology behind the programs. There are no off the shelf solutions or consultants you can buy to make this problem go away - it needs to be a core focus and competency for any institution. The ones who think they can pay or outsource the problem away, won’t survive. This is expensive and hard, and part of why we're seeing so much thrash in the space today.”

As a result, the fixed costs of running these partnerships are not only being passed on to the non-bank company, but are increasing too. In other words, the model where non-bank companies view a partner bank as a commoditized infrastructure provider that they could pay on a SaaS basis will slowly disappear. Instead, non-bank companies will start absorbing these costs, potentially reducing the profitability of pursuing BaaS-led growth for early-stage companies.

The Fintech Slowdown

The early-stage market in fintech has experienced a significant slowdown since 2021, with venture investment into fintech startups declining by 32% year-over-year in 2022, and an additional 42% in 2023. In addition, many of the largest VC-backed fintech companies, from Brex to PayPal, have also recently announced layoffs.

For BaaS providers, this means that a large portion of their potential non-bank companies are prioritizing cash flow and profitability over growth-at-all-costs. As highlighted by an October 2023 McKinsey report:

“The last era was all about firms being experimental—taking risks and pursuing growth at all costs. In the new era, a challenged funding environment means fintechs can no longer afford to sprint. To remain competitive, they must run at a slower and steadier pace.”

As a result, there exist fewer companies interested in adopting BaaS solutions due to the high initial fixed costs. Additionally, the early-stage companies who have engaged in BaaS partnerships are at a high risk of churn as the bar to raise additional rounds of financing has risen significantly. This challenge was emphasized by Eric Kaplan, of Bessemer Venture Partners, in an interview with Contrary Research:

“It is definitely a challenging time to be a company building in the embedded finance world because there are fewer fintechs to sell to. Many of the fintechs have reoriented their GTM mindset and this leads to fewer customers for embedded finance companies. But, we are also at a moment in time, with AI, where you can now operate downmarket much more effectively.”

Future of BaaS

It has become increasingly clear that the future of BaaS will likely involve direct, multibank partnerships.

Why Direct? As regulatory scrutiny continues and banks become increasingly alert to the risks, there is no feasible way to ensure a fully compliant BaaS partnership while also having many layers of abstraction. Banks and companies must know what counterparts they are working with. As a result, non-bank companies – especially early-stage startups that are trying to move quickly – will have to reconstruct their bank partnerships; a partner bank can no longer be viewed as a commoditized infrastructure provider.

Why Multibank? As we’ve seen over the past few years, there is risk in partnering with just one bank; the cost and time taken to switch between multiple banks is high and if a partner bank suddenly receives a consent order, your entire business is at risk. Thus, many believe that partnering with multiple banks is key to mitigating the contagion risk that exists in BaaS. With that said, it is important to highlight that multibank partnerships sometimes aren’t necessary, or even possible, for certain financial products such as deposit accounts.

So, what model will define the future of BaaS? There are two likely paths forward:

The Marketplace Approach: Currently, companies like Treasury Prime, Unit, and Synctera largely possess the types of direct, multibank partnerships described above. While these companies are differentiated by several key factors, ranging from the extent of their involvement with compliance to their overall positioning between banks and non-banks, what they have in common is that they are all focused on building a network that enables direct relationships between partner banks and non-bank companies. This positioning has enabled them to keep a compliance-first approach.

BaaS-First Banks: These players represent a mixed solution – a chartered bank that has the necessary technical capabilities combined with the compliance expertise to enable non-bank companies to embed financial products. This approach therefore can represent the best of both worlds, but the primary drawback is that there are only a limited number of players. As of February 2024, Lead Bank, Column, and Cross River are the three most well-known BaaS-first banks. Additionally, another drawback is that existing players do not currently have a multibank model built into their operating model. But, from our interviews, we see the potential for multibank collaboration to emerge if more BaaS-first banks can enter the market.

While we’ve outlined two promising models here, there is no single correct model in BaaS. Instead, the model that makes the most sense depends on the customer type that is being served.

In particular, based on our conversations with both founders and investors, we believe that BaaS-first banks are well-positioned to win the market for large fintech companies and customers with complex fund flows. Such companies, like Brex and Ramp*, have very specific use cases that require custom implementations and a strong partner-bank relationship. This model is ideal for serving those large customers.

For large, non-fintech companies like Toast and Lyft, the marketplace approach will likely emerge as the winner. These non-fintech companies have relatively standard products and since they aren’t fintech-first, they will benefit from the support that a BaaS provider can give.

For early-stage companies, the bar has been raised significantly – teams now need a minimum amount of funding, a strong team with fintech experience, and a unique value proposition. Of those companies that meet that criteria, working with a BaaS provider will also likely be the strategy that prevails due to the support provided. However, more broadly, we expect to see fewer of these companies embed financial products due to rising costs of compliance and the bar for execution.

Sheel Mohnot, General Partner at Better Tomorrow Ventures, summarized this belief that different customers benefit from different models in an interview with Contrary Research:

“There are different models for different types of customers. One of our portfolio companies is in banking and they are about to add a direct relationship with Column. That totally makes sense for them given what they are building. But, if you are a vertical-SaaS company, it isn’t worth directly integrating with a bank. For those companies, working with a Unit and one of their bank partners is the best option.”

As a result, many in the industry believe that there can be multiple billion-dollar businesses that emerge in this space. As described by William Hockey, CEO of Column:

“The market is huge and there is room for a number of big winners here. We're still in the early innings, companies are trying different models, the market and regulators are providing feedback, and the ecosystem will iterate and get stronger. Banking, and fintechs working with banks, is a very long term game. That said, it requires a large amount of capital, talent, focus and time - the expectations are high and room for error at zero. We'll likely continue to see turnover from all types of players as some models go away.”

The Future Of Compliance

In terms of regulatory action in BaaS, several of the people we spoke with believe things will get worse before they get better, but that regulatory action is actually a largely positive factor for the space. Certain players in BaaS have not built out fully-compliant solutions and these actors will continue to be at the center of consent orders. But, as more guidance is released and certain less committed banks exit the space, we believe that the industry will mature and identify clear compliance protocols. This belief is also shared by Amit Kumar, partner at Accel:

“Regulatory scrutiny is normal. You’re dealing with consumers and people’s money. BaaS companies need to embrace this and win. If you want a high level of impact and to replatform how Americans bank and manage their money, it’s actually a great thing that regulators are getting involved to set guardrails. The industry will benefit from that in the long-run.”

And as the industry becomes more focused on compliance, many expect that we will see fewer BaaS providers in the market. Put simply, the bar of execution in BaaS is higher than in most other categories; BaaS companies not only have to be excellent at compliance and technology, but they also have to perfect the go-to-market side and build a balanced marketplace. This will prove increasingly difficult for traditional middleware providers who are operating from a deficit of trust due to regulatory challenges and public disputes they have experienced.

Is BaaS Dead?